Image taken by Ricardo Martin who granted free use of his beautiful pictures. (I love it when people do that!) http://cromavista.ricardomartin.info/castrillo-de-los-polvazares/001

“Adónde vamos?” I asked, sitting in the car with a group of my friends. It was a Saturday morning and we were off on another adventure in their quest to “Show Christy all of Spain in 9 months.” It was only natural that I should wonder where we were heading this time.

“Iremosaunpueblollamadocastrillodelospolvazaresacomercocidomaragato.”

Right. I nodded, giving my friend a close-lipped smile of bewilderment, eyebrows raised. Why was it that after all those years of studying high school and college level Spanish, and living in the country for almost 6 weeks, it still sounded like they just strung random syllables together, pronouncing them quickly to confuse me? I think I understood two words in that entire phrase, “pueblo” and “de.”

“Don’t worry,” my friend laughed, switching to her stilted English, “Jou will like eet.”

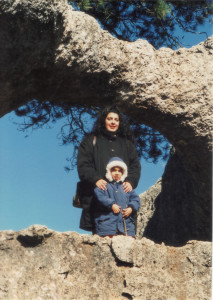

And I knew she was right—I had never imagined that this little city of León, situated northwest of Madrid, fairly close to Portugal, would have so many treasures within a radius of one to two hours drive. So we headed northwest, meandered over some mountains, into the area known as Astorga, turned down a gravelly road and next thing I know we arrived at this parking lot in the middle of nowhere. Literally. Nothing but trees and the dust that our tires had kicked up, still hanging in the air.

“I thought we were going to a pueblo,” I said, baffled.

“Yes, it’s over there,” said my friend, pointing the way over a stony bridge. “No cars can go in there so we park here and walk”

I nodded and followed, and soon I saw the sign, “CASTRILLO DE LOS POLVAZARES.” Clearly the name of this little town was inversely proportional to its size! The whole village was made of red rocks. The streets were cobbled with them, sporting deep indentations in the middle (maybe 8 inches deep.) “For the water to run off the road and out of the pueblo easily,” another friend explained. There were no sidewalks, but next to several houses, which were made of the same reddish rock and crouched right next to road, were stone benches that seemed to be roots that the houses were putting down to usurp more of the narrow road. I kept thinking that Fred and Wilma (who are Pedro and Vilma in Spanish) would have been very happy here.

“How old is this place?” I asked, thinking that surely it was pre-Roman, as so much of what I had already seen in León. It was curious that the only wooden parts, doors and shutters on the windows , were all painted Kelly green, and the rest were chocolate brown. It worked.

Image also taken by Ricardo Martin who granted free use of his beautiful pictures. http://cromavista.ricardomartin.info/castrillo-de-los-polvazares/001

“Oh, this is a modern village,” my friend assured me, “Three hundred years old at the most.” She kept a straight face and I realized she was serious. I smiled and shook my head. I’ve since learned from Wikipedia that she did underestimate a bit–apparently it was destroyed by a flood in the 1500’s, and re-built after that on the same spot (you don’t see the grooves in the road very well in this picture–they are much deeper than what is shown here.)

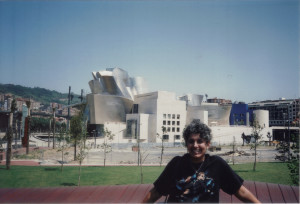

After walking around for a bit, (and admiring the storks in their nest on the belfry of the stone church) we went to one of the several restaurants in town to eat the typical dish called “cocido maragato.” It’s basically a chick-pea soup with the typical meats (chorizo sausage, ribs, bacon, etc.) but what’s different is that it’s all served separately, and in a backwards order compared to what you would get in a restaurant anywhere else in Spain—first the plate of meat, then the chickpeas, and lastly a chicken broth with fine noodles, all complemented with the house red wine (which comes free with the meal, as in all of Spain) and crusty Spanish bread. The story of why they eat it backwards has something to do with the people that lived there, the “Maragatos” who traveled all day to sell their wares, and were so hungry when they finally got back home that they didn’t want to eat the soup first, so they would dive into the meat…by the time they got to the soup, it was practically dessert. Anyway, it was very delicious (there’s a picture below) and I definitely advise that visitors to this tiny village come with an appetite.

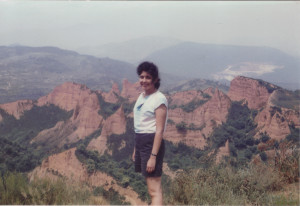

This is a great excursion to pair with a visit to Las Médulas, after which you could suggest going to this village for lunch by saying, “Iremos a Castrillo de los Polavazares a comer cocido maragato,” and everyone would wonder at your prowess.

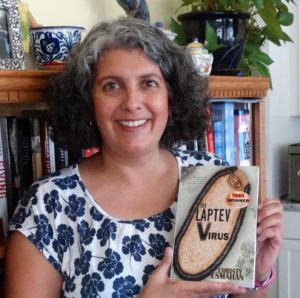

If you enjoyed this blog post, you might also like my series of novels, Bueno, Sinco and Brujas, which takes place in Santander, Spain.