Many thanks to Asturgeografic (https://www.facebook.com/Asturgeografic) for kindly agreeing to let me use their photo for this post!

“Can you tell us which way to the dolmen?” my friend asked the woman standing outside the last house of the village. She seemed very old to me, though my best guess now is that she was in her 50’s. She shooed the clucking chickens away and stepped a bit closer, asking us to repeat the question. We were in Galicia, which is in the northwest corner of Spain, the part right above Portugal, and it was clear that she rarely spoke Castilian Spanish. Instead, like everyone in the villages we had been traveling through, she spoke Galician (called Gallego in Spanish), which is a language that is like a hybrid between Portuguese and Spanish, with some Celtic words mixed in.

“Here, let me finish feeding the chickens and I’ll take you there. It’s out in the field,” she said in a raspy voice, once she had finally understood what we were asking. Half of her words were in Galician, but from her good-natured smile I could guess what my friend later confirmed in translation.

We waited patiently while she changed from her short waterproof boots into wooden shoes, zuecos, with 3 heels: the regular one you’d expect to see at the back of the shoe, and two more under the ball of the foot. The toes of the zuecos (pictured below this paragraph) curled upward like classic Dutch shoes. Apparently these ancient clodhoppers are very good for walking through muddy fields. We pulled our coats tighter around ourselves as the misty rain thickened, but she seemed not to notice the weather as she stood there in her flowered house dress and cardigan sweater. Her skin was a weatherworn red, and a few pieces of unruly hair escaped from the kerchief she had tied around her head.

“It’s about a kilometer and a half away—twenty minutes or so,” she said as she started walking, We thanked her for interrupting her farm chores to help us out and followed her single file as she strode down a narrow footpath through the grassy field. “We rarely ever get anyone out here to see it,” she said.

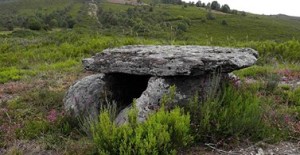

My friend had described dolmens to me—ancient stone structures built by Neolithic people thousands of years ago. According to Wikipedia, archaeologists still don’t know who built them—and without knowing that, there’s no way to tell why they would have done so or how they accomplished the feat. Most seem to be 6,000-7,000 years old, though that’s still a guess too. Some have yielded human remains, but there’s no way to tell whether these remains belong to the humans who assembled these megaliths.

The rain had let up by the time we reached the structure. “It’s a small one,” she explained, almost in apology. “There are bigger ones in other parts of Galicia, but this one is small.”

There were two massive stones, obviously weighing dozens of tons each, standing wedged up on their sides, like two walls, and then another large stone on top, kind of like a roof. It was different from anything I’d ever seen, and even now, as I think back on that experience, it once again takes my breath away. There, in the middle of the lonely windswept field, with the low lead-colored clouds brushing our heads, the haunting stone structure felt like it was full of magic. I felt as if our ancestors were reaching forward thousands of years in time to make us stop and look and wonder.

What were these dolmen used for? Were they some sort of altars for worship? Were they tombs? They certainly were too small to be houses—and too much work. The closest quarry from which the stones for this dolmen came was probably 30 kilometers away. And the wheel had not been invented yet. So how did the pre-historic people get these huge stones out to the middle of this field and then stand them up? What drove them to do this?

After our excursion I learned that not only are dolmens to be found all over Spain, but also all around Western Europe, in the Middle East and Asia, especially Korea. Wikipedia says that 40% of all known dolmen in the world are in Korea. And, apparently in Russia new dolmens are discovered in the mountains regularly. Again, we don’t know who built them or why, though most scientists point to sepulchral use.

As you wander around Spain searching for dolmens, be sure to also check out the stone circles (Stonehenge is the most well-known of these, but there are others scattered all over the UK, as well as in Spain and Portugal) and the mehnir , which are huge upright stones, each weighing thousands of pounds. Most are not in areas that are quite so out-of-the-way as the dolmen I describe above. And as you stand there next to one, see if you can also feel the magic and power of these places.

I would love to hear any dolmen stories you may have!

If you enjoyed this blog post, you might also like my series of novels, Bueno, Sinco and Brujas, which takes place in Santander, Spain.

2 comments

I’m sure you know the French Asterix comic books. Obelix (faithful sidekick to Asterix) is always pictured carrying a menhir. He is super strong because he fell into the cauldron of magic potion when he was a baby. http://www.asterix.com/index.php.fr Is a dolmen the flat part and the menhir the upright stones? Or maybe the dolmen is the term for the structure as a whole …

Author

Yes, Kathy, I love Asterix and Obelix. I first learned about these comics in Spain–they read them a lot there. The dolmen is the three stones together, making the whole structure. Menhirs are the rocks that stand up straight, and I believe they never had another rock on top–they are monoliths. There are many sites with menhirs throughout Europe. I had forgotten Obelix carried one! It’s a great visual of how strong he is!