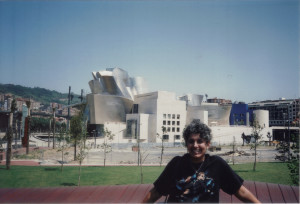

This is me with the Guggenheim Museum of Bilbao in the background, in 2003. If you look carefully you can see some construction debris. This has since been cleared, and the trees are much larger now.

“It’s supposed to be a ship, you know, because of the wharf and shipyard that used to be here. See how that part over there goes to the other side of the bridge too?”

“Well, I think it looks more like a flower—like one of those roses you see made out of metal.”

“No, no” said the third student, “It’s definitely a bird’s nest. Look at how the sticks are going every which way, like a gigantic stork’s nest.”

It was 1995 and we were taking a hard-hat tour of the new Guggenheim museum which was being built in the heart of Bilbao, along the Nervión River. I wish I still had the pictures I took of the fantastically curved and arched steel beams that reached up, willy-nilly, as if trying to snag the low-lying rain clouds that love to drizzle onto the city. While my students chattered on, all I could think was that there was no way, no way, the construction crews were going to be able to attach walls to those insanely curved support beams.

As I mentioned in my last blog post about Bilbao, I had the good fortune to live just a ten minute walk from the museum, so I made a point of sauntering by the construction site every few days, sure that I would eventually see a wrecking ball and crane knocking down the parts that had been built wrong. Maybe the plans had been distorted in the FAX machine? Maybe Frank Gehry, the architect, had spilled coffee on them and the ink had run? Or maybe the construction team was trying to use faulty beams that got warped when they were being poured or assembled? There had to be a logical explanation. After all, just a few kilometers away, everyone had driven by the hospital, fifteen stories high, that had been built on sandy, unstable terrain and therefore never occupied. Millions of pesetas, wasted. And what about the cement pillars for the overpass on the A-1 highway between Burgos and Bilbao, which had been placed 100 meters from either side of the road it was to connect? Another cement monument to plans gone wrong. This crazy museum was surely one of those huge mistakes that would be set in stone for posterity to scoff at.

Reality check: The website dedicated to Guggenheim museums around the world says, “Due to the mathematical complexity of Gehry’s design, he decided to work with an advanced software [program that was] initially conceived for the aerospace industry.” (1) This website has an extremely cool video and some great photos—including ones from the construction phase, so definitely check it out—the link is below. And, a publication by the Harvard Design School states, “Gehry’s design featured complex shapes that called for innovative construction methods. It became clear that the contractors were to play a central role in developing technical solutions that met the design challenges.” (2) No kidding! No one—not even the great architect, Antoni Gaudí, whom I discussed in a previous blog post—had been harebrained enough to try to build something like this. Of course the contractors would have to figure out how to build it as they went along!

Back to my story: Weeks turned into months with no sign of a wrecking ball or crane. The workers continued welding and soldering beams, creating what looked like an incredibly huge roller coaster, and pretty soon after that, there were solid surfaces blocking my view of the interior. Then it was time to put up the shiny surface—titanium. First there was a huge, very public debate about from where to purchase the titanium—I think they were supposed to get it from Russia but the price changed and they could no longer afford the thousands of sheets they would need. I remember the saga fondly—everyone in Bilbao, on every street, in every bar, and in all the shops, was speaking of the titanium problem for weeks on end—but I don’t remember the outcome! In any case, they finally figured out a solution, and then the titanium arrived. Sheets that were 0.4mm thick—just a bit thicker than aluminum foil—were cut to right size, and then stapled on. For weeks on end we could hear the clip-clip-clip of the pneumatic staple guns as they worked, sheet by sheet, to get all 33,000 onto the surface.

As the museum is located right next to one of Bilbao’s numerous bridges, there was some concern that a mirrored surface would reflect sunlight into the eyes of drivers, placing them in peril—NOT that there’s that much sun in Bilbao on a regular basis—but just in case, so it was a good thing that Gehry opted for a more muted, stippled look. Limestone and glass completed the other surfaces and we were left with one of the most stunning buildings I’ve ever seen.

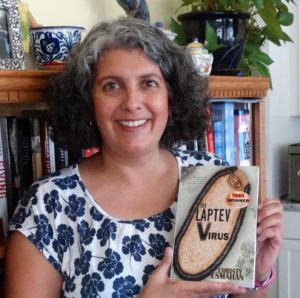

Two of the characters in my book, two young teachers from the U.S., Pamela and Melissa, take a trip to Bilbao and tour the Guggenheim. You’ll have to let me know what you think of that part of the book.

Meanwhile, let me add my voice to the millions of people who have said, “Congratulations, Bilbao! Congratulations, Frank Gehry. What a beautiful sight!” Be sure to check out the links below for some very cool pictures!

(2) “Managing the Construction of the Museo Guggenhiem Bilbao”, published by the Harvard Design School, Center for Design Informatics

If you enjoyed this blog post, you might also like my series of novels, Bueno, Sinco and Brujas, which takes place in Santander, Spain.

1 ping

[…] « Guggenheim Museum of Bilbao […]